9 New Technologies Needed to Fight Climate Change

Some fossil fuel defenders argue that transitioning to a low-carbon, net-zero world is impossible because the technology to do so does not exist. On the other hand, many environmentalists claim we have all the technologies needed to solve the climate crisis, and simply lack the political will to adopt them.

The truth is somewhere in between. We have already commercialized many technologies necessary to fight climate change (wind turbines, solar panels, hydroelectric dams, nuclear power stations, geothermal energy, heat pumps, electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, etc.). But there remain some significant gaps in our low-carbon portfolio where new technologies are genuinely needed.

Here’s a look at the top nine new technologies needed to fight climate change:

9. Green Fertilizer

Synthetic fertilizer production represents 2% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, as both the energy and the hydrogen molecules used to manufacture its precursor - ammonia - typically come from burning fossil gas.

Ammonia can be made using low-carbon, renewable electricity instead. But the process to create this ‘green ammonia’ is currently 50% to 150% more expensive than the conventional method. Technologies that lower the cost of green ammonia are needed to decarbonize this oft-overlooked sector.

8. Sustainable Marine Fuel

Large ships currently run on heavy fuel oil (HFO), which is essentially the dirtiest distillate of crude oil left over after the cleaner distillates are sold for aviation and automotive fuels. Marine shipping represents about 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and additionally creates local air pollution in port communities.

Replacing HFO will be difficult. Batteries don’t have the energy density to last an entire intercontinental journey and (unlike automobiles or trucks) ships cannot be recharged en route. Nuclear propulsion has worked very well on aircraft carriers, but the security challenges in civilian ships are likely insurmountable.

Low-carbon liquid fuels synthesized using renewable electricity (electrofuels) will likely be necessary. These fuels - which include ammonia, methanol, or even a synthetic hydrocarbon - would allow ships to achieve nearly zero emissions without radically changing ship design.

7. Livestock Methane Abatement

As strange as it might seem, between 5% and 7% of greenhouse gas emissions are emitted by cows. Bacteria inside a cow’s gastrointestinal system generate methane, a potent greenhouse gas, which is subsequently released by the cow’s eructations (burps) or defecations. Multiplied by the 1.5 billion cattle in the world, this extra methane adds up to a serious climate problem.

Persuading the world to give up beef and dairy seems an impossible task. So the search is on for a technological solution. Feed additives that interfere with methane production and thus reduce emissions are beginning to appear on the market. Vaccines to target the methane-generating bacteria themselves are also under development. Selective breeding techniques could also be used one day to create a breed of lower-emission cows.

6. Seasonal Storage

Electricity generation makes up 30% to 35% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Fully decarbonizing this sector means replacing existing fossil generation with clean, low-carbon electricity 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days of the year. And this task in turn requires firming the intermittent generation of resources like wind and solar.

Diurnal renewable intermittency will soon be solved with lithium-ion batteries. But wind and solar also display seasonal variability. The problem is particularly acute for solar energy in winter at high latitudes (e.g. the northern parts of Europe and North America) or areas that experience seasonal monsoon cloudiness (India and Indonesia).

The only existing seasonal storage technology is pumped hydro, a form of hydroelectric generation that combines a reservoir, a pumping system, and a hill to make a closed-loop storage system. But pumped hydro has large capital costs and requires a very specific geography. More exotic ideas like generating green hydrogen in summer and burning it in winter would be eye-wateringly expensive with current technology.

Solving seasonal storage is not impossible. But it is one of the pieces of the climate puzzle currently lacking a clear technological pathway and needing the most innovation.

Be sure to sign up to get Earthview in your inbox:

And consider a paid subscription to get premium analysis and support the work we’re doing!

5. High-Temperature Industrial Heat

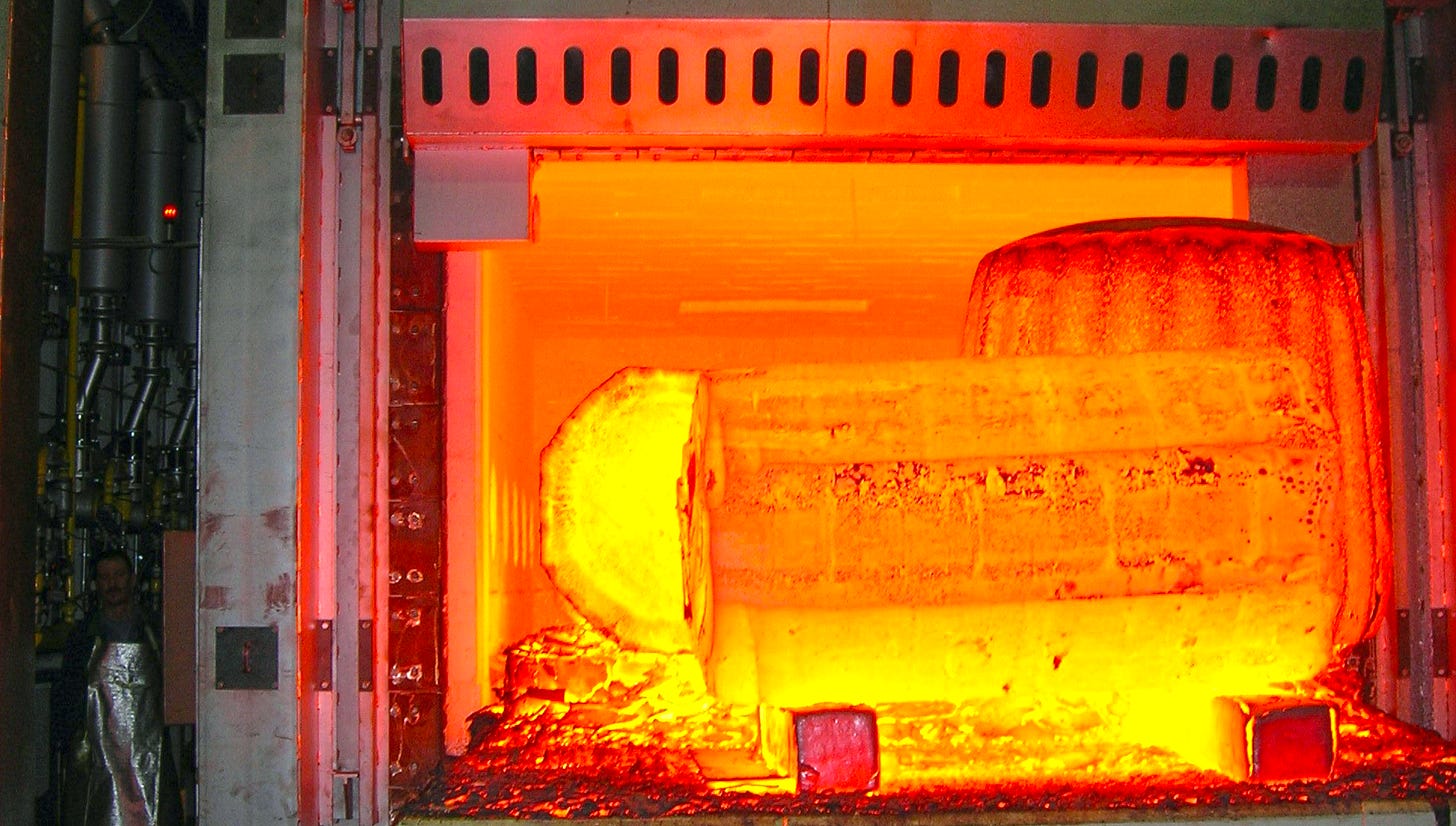

A number of industrial processes - glassmaking, papermaking, sterilization, baking, brickmaking, etc. - require heat. Most of that heat is currently provided by combusting fossil fuels like coal or fossil gas.

At lower temperatures (below 400° C / 750° F), electric technologies like heat pumps and resistance heaters already exist to replace fossil fuels. But achieving higher temperatures will likely require combusting some sort of low-carbon fuel.

The likeliest candidate is green hydrogen made with renewable electricity. Although creating green hydrogen is straightforward, it is currently expensive. And the task of using it to decarbonize industrial heat is especially challenging as specific processes for each application must be adapted to use the new fuel.

4. Multi-Day Storage

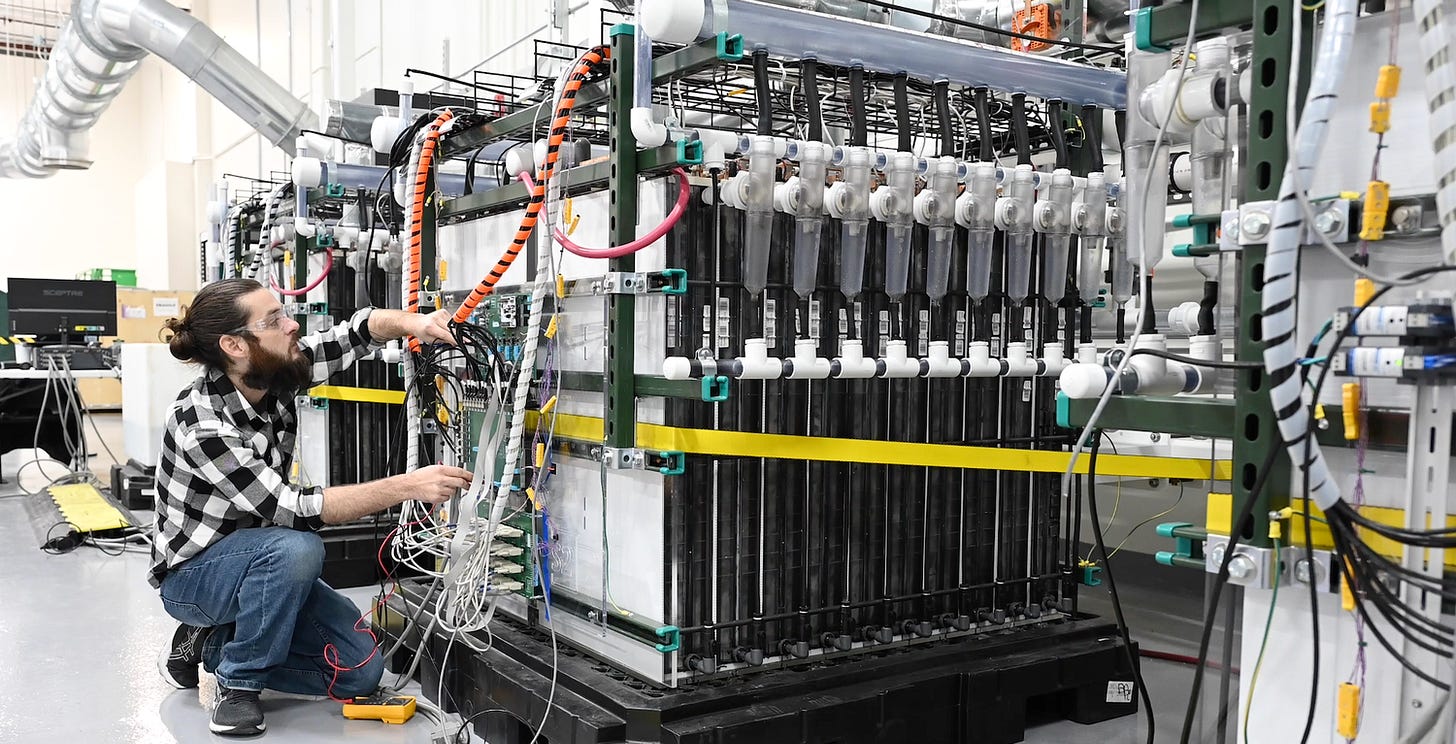

Firming variable resources like wind and solar is a necessary step in the energy transition away from fossil fuels. Diurnal intermittency will soon be fully solved by lithium batteries. But this standard chemistry may be too expensive to use in multi-day applications, as lower cycling rates require cheaper technology to be economically viable.

A wide array of new storage technologies are competing to fill this gap in the market. Perhaps the furthest-along is iron-air batteries, which are much heavier than lithium-ion (and so unsuitable for automotive applications) - but aim to be as much as 50% cheaper. Other contenders are compressed gas storage systems like that of Italian startup EnergyDome, which inflates and then deflates a giant bladder to store energy.

Iron-air batteries like those made by Form Energy are being rolled out now to utility-scale energy projects. Eventually, multi-day batteries could be sold to consumers both for whole-home backup and an additional source of storage for the grid.

3. Sustainable Aviation Fuel

The aviation sector represents only 2.5% of global emissions. But it is one of the fastest growing sectors and this share is projected to increase substantially by 2050.

Decarbonizing aviation, however, is a fiendishly difficult problem due to the very high energy densities required to power commercial aircraft. Batteries may improve and offer a solution for short-haul flights. But they are unlikely to ever reach the energy densities needed for long-haul, intercontinental routes.

The solution - like in shipping - will probably be electrofuels. Any hydrocarbon (including jet fuel) can be synthesized from thin air using renewable electricity and carbon and hydrogen atoms pulled from the atmosphere. This form of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) still emits carbon dioxide at its point source. But the net impact of this carbon emission is zero as the molecules were originally pulled from the air in the first place.

Synthesizing high-quality, low-carbon SAFs and integrating them into the global aviation system is possible. Doing all this cheaply, however, will require technological improvements to the process and ramping up production volumes to reap economies of scale.

2. Green Steel

Around 7% to 9% of global GHG emissions come from steelmaking, which uses coal both for energy and as a chemical reductant. Replacing coal in this process is a vital step to getting to net-zero, particularly as low-carbon technologies like wind turbines and electric vehicles are made from steel and incorporate its emissions.

The likeliest contender to replace coal is a new process which uses Hydrogen Direct Reduction (H-DRI) to produce sponge iron and then an Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) to transform this sponge iron into virgin steel. Swedish steelmaker Stegra aims to produce commercial quantities of this ‘green steel’ in 2026 and other steelmakers have plans to follow suit.

1. Green Cement

Cement - used primarily to produce concrete - accounts for 8% of global GHG emissions. 40% of these emissions come from the fossil fuels used to power the process. 60% of these emissions, however, are completely unrelated to fossil fuels. They are emitted directly from the input materials themselves, as limestone rock releases carbon dioxide when heated.

The cement industry is the only sector in which some form of carbon capture is considered a serious decarbonization option. Capturing some of the carbon released by the limestone and injecting it back into the finished concrete product could provide partial mitigation. Alternative cement chemistries with lower carbon profiles and the exotic option of creating carbon-neutral biogenic limestone using algae are also being explored.

Of all sectors, the race to decarbonize cement remains the most difficult and most open to new technological solutions.

Be sure to sign up to get Earthview in your inbox:

And consider a paid subscription to get premium analysis and support the work we’re doing!